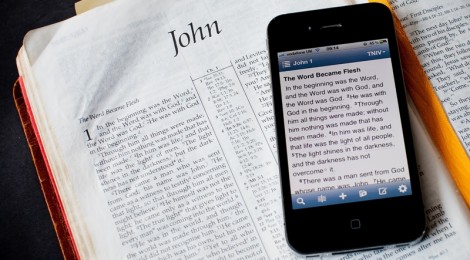

Many concern things like personal struggles or dealing with anxiety, for example – rather than promoting the glory of God. The most popular Bible verses bookmarked, highlighted and shared on social media via YouVersion’s app are frequently those which reflect the secular and inclusive ideals of moralistic therapeutic deism. Bible verses are also subject to popularity contests, where their acceptability to a wide audience can dictate their spread. Sharing Bible verses on social media lets worshippers find their own readings rather than sitting through ones chosen by a priest every Sunday. “He stands behind them and allows them to get on with their own lives rather than Jesus, who comes in and interferes with everything.” “Millennials prefer this generalised picture of God rather than an interventionist God, and they prefer God to Jesus, because he’s non-specific,” says Phillips. A lot of people who consider themselves to be active Christians may not strictly even believe in God or Jesus or the acts described in the Bible. And the ability to pick and choose means they can avoid doctrine that does not appeal. In the US, one in five people who identify as Catholics and one in four Protestants seldom or never attend organised services, according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Centre.Īpps and social media accounts tweeting out Bible verses allow a private expression of faith that takes place between a person and their phone screen. For many, it’s no longer necessary to set foot in a church. Yet at the same time, a separate strand of Christian practice is booming, buoyed by the spread of social media and the decentralisation of religious activity. If you take Genesis as an account of six days of creation, for example, you will need to believe that science is wrong, says Phillips. Some think that overly literal interpretations of religious texts can lead to fundamentalism. You don’t flick through: you just go to where you’ve asked it to go to, and you’ve no sense of what came before or after.” With a digital version you don’t get any of that, you don’t get the boundaries. “But you know that Revelations is the last book and Genesis is the first and Psalms is in between. “If you go to the Bible as a paper book, it’s quite large and complicated and you’ve got to thumb through it,” says Phillips. But reading the Bible in this way could be changing people’s overall sense of it. “To some extent, the mobile phone Bible is now replacing the book Bible.”Īccording to the company behind YouVersion, people have spent more than 235 billion minutes using the app and have highlighted 636 million Bible verses. Those digitised Bibles then made their way onto phones. “One of the first things Christians did with the computer was to put the Bible into digital formats,” says Phillips. Similarly popular apps exist for the Torah and Koran. Many people scrolling through their phones in Christian churches are probably looking at a Bible app called YouVersion, which has been installed more than 260 million times worldwide since its launch in 2008. “But that technology has shaped religious people themselves and changed their behaviour.” Faiths are adopting online technologies to make it easier for people to communicate ideas and worship, says Phillips. And they are changing the way people practise their religion. The ubiquity of smartphones and social media makes them hard to avoid, however. The rise of apps and social media is changing the way many of the world’s two billion Christians worship – and even what it means to be religious.

#BIBLE STUDY IMAGES CELL PHONE UPDATE#

This more relaxed approach to phones is not the only tech-related update the Church has undergone in the past few years. “The attitude has changed because to restrict people from mobile phone use now is to ask them to cut their arm off.” “They allow people to take photos, to use phones for devotional reasons – whatever they want to do,” says Phillips. Next year Durham Cathedral will have been standing for 1,000 years. “I was a bit miffed about that,” says Phillips, who is director of the Codec Research Centre for Digital Theology at Durham University in the UK. Phones were not allowed in the holy place, and the individual who accosted him would not believe that he was using his phone for worship and asked him to leave. He had been reading the Bible on his mobile phone in the pews.

When the Reverend Pete Phillips first arrived in Durham nine years ago, he was ejected from the city’s cathedral.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)